An unfair advantage: multi-tenant queues in Postgres

Alexander Belanger

Published on April 18, 2024

TL;DR - we’ve been implementing fair queueing strategies for Postgres-backed task queues, so processing Bob’s 10,000 files doesn’t crowd out Alice’s 1-page PDF. We’ve solved this in Hatchet and Hatchet Cloud so you don’t have to — here’s a look at how we did it.

Introduction

We set the scene with a simple user request: they’d like to upload and parse a PDF. Or an image, CSV, audio file — it doesn’t really matter. What matters is that the processing of this file can take ages, and scales ≥ linearly with the size of the file.

Perhaps you’re an astute developer and realized that processing this file might impact the performance of your API — or more likely, the new file upload feature you pushed on Friday has you explaining to your family that nephew Jimmy’s baseball game on Saturday will have to wait.

In the postmortem, you decide to offload processing this file to somewhere outside of the core web server, asynchronously on a new worker process. The user can now upload a file, the web server quickly sends it off to the worker, and life goes on.

That is, until Bob decides to upload his entire hard drive — probably also on a Saturday — and your document processing worker now goes down.

At this point (or ideally before this point), you introduce…the task queue. This allows you to queue each file processing task and only dispatch the amount of tasks each worker can handle at a time.

But while this solves the problem of the worker crashing, it introduces a new problem, because you’ve intentionally bottlenecked the system. Which means that when Bob uploads his second hard drive, a new issue emerges - Alice’s 1-page file upload gets stuck at the back of the queue:

You’re now worried about fairness — specifically, how can you guarantee fair execution time to both Bob and Alice? We’d like to introduce a strategy that’s easy to implement in a Postgres-backed queue — and more difficult in other queueing systems — deterministic round-robin queueing.

The setup

Let’s start with some code! We’re implementing a basic Postgres-backed task queue, where workers poll for events off the queue at some interval. You can find all the code used in these examples — along with some nice helper seed and worker commands — in this repo: github.com/abelanger5/postgres-fair-queue. Note that I chose sqlc to write these examples, so you might see some sqlc.arg and sqlc.narg in the example queries.

Our tasks are very simple — they have a created_at time, some input data, and an auto-incremented id:

-- CreateEnum

CREATE TYPE "TaskStatus" AS ENUM (

'QUEUED',

'RUNNING',

'SUCCEEDED',

'FAILED',

'CANCELLED'

);

-- CreateTable

CREATE TABLE

tasks (

id BIGSERIAL NOT NULL,

created_at timestamp,

status "TaskStatus" NOT NULL,

args jsonb,

PRIMARY KEY (id)

);The query which pops tasks off the queue looks like the following:

-- name: PopTasks :many

WITH

eligible_tasks AS (

SELECT

*

FROM

tasks

WHERE

"status" = 'QUEUED'

ORDER BY id ASC

FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED

LIMIT

COALESCE(sqlc.narg('limit'), 10)

)

UPDATE tasks

SET

"status" = 'RUNNING'

FROM

eligible_tasks

WHERE

tasks.id = eligible_tasks.id

RETURNING tasks.*;Note the use of FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED: this means that workers which concurrently pull tasks off the queue won’t pull duplicate tasks, because they won’t read any rows locked by other worker transactions.

The polling logic looks something like this:

type HandleTask func(ctx context.Context, task *dbsqlc.Task)

func poll(ctx context.Context, handleTask HandleTask) {

for {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return

case <-time.After(5 * time.Second):

tasks, err := queries.PopTasks(ctx, pool, 10)

if err != nil {

log.Printf("could not pop tasks: %v", err)

continue

}

for _, task := range tasks {

handleTask(ctx, task)

}

}

}

}The ORDER BY id statement gives us a default ordering by the auto-incremented index. We’ve now implemented the basic task queue shared above, with long-polling for tasks. We could also add some nice features, like listen/notify to get new tasks immediately, but that’s not the core focus here.

Fair queueing

We’d now like to guarantee fair execution time to Bob and Alice. A simple way to support this is a round-robin strategy: pop 1 task from Alice, 1 task from Bob, and…Bob’s your uncle? To achieve this, we can imagine separate queues for each group of users — in this case, “purple,” “orange” and “green”:

Even though we’re essentially creating a set of smaller queues within our larger queue, we don’t want workers to manage their subscriptions across all possible queues. The ugliness of adding a new queue per group should be abstracted from the worker, which should use a single query to pop the next tasks out of the queue.

To define our groups, let’s modify our implementation above slightly: we’re going to introduce a group_key to each table:

CREATE TABLE

tasks (

id BIGSERIAL NOT NULL,

created_at timestamp,

status "TaskStatus" NOT NULL,

args jsonb,

group_key text,

PRIMARY KEY (id)

);The group key simply identifies which group the task belongs to — for example, is this one of Bob’s or Alice’s tasks? This can refer to individual users, tenants, or even a custom group key based on some combination of other fields.

First attempt: PARTITION BY

Let’s try our hand at writing a query to do this. While we have a few options, the most straightforward solution is to use PARTITION BY. Here’s what we’d like the query to look like:

WITH

eligible_tasks AS (

SELECT

t.id,

t."status",

t."group_key",

row_number() OVER (PARTITION BY t."group_key" ORDER BY t."id" ASC) AS rn

FROM

tasks t

WHERE

"status" = 'QUEUED'

ORDER BY rn, t.id ASC

LIMIT

COALESCE(sqlc.narg('limit'), 10)

FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED

)

UPDATE tasks

SET

"status" = 'RUNNING'

FROM

eligible_tasks

WHERE

tasks.id = eligible_tasks.id AND

tasks."status" = 'QUEUED'

RETURNING tasks.*;This assigns a row number of 1 to the first task in each group, a row number of 2 to the second task in each group, and so on.

However, if we run this, we’ll get the error: ERROR: FOR UPDATE is not allowed with window functions (SQLSTATE 0A000) . Easy, let’s tweak our query to solve for this - we’ll load up the rows with PARTITION BY and pass them to a new expression which uses SKIP LOCKED:

WITH

ordered_tasks AS (

SELECT

t.id,

t."status",

t."group_key",

row_number() OVER (PARTITION BY t."group_key" ORDER BY t."id" ASC) AS rn

FROM

tasks t

WHERE

"status" = 'QUEUED'

ORDER BY rn, t.id ASC

LIMIT

COALESCE(sqlc.narg('limit'), 10)

),

eligible_tasks AS (

SELECT

t1.id

FROM

ordered_tasks t1

FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED

)

UPDATE tasks

SET

"status" = 'RUNNING'

FROM

eligible_tasks

WHERE

tasks.id = eligible_tasks.id AND

tasks."status" = 'QUEUED'

RETURNING tasks.*;…but not so fast. We’ve introduced an issue by adding the first CTE (Common Table Expression - the queries using the WITH clause). If we run 3 workers concurrently and log the number of rows that each worker receives, with a limit of 100 rows per worker, we’ll find only 1 worker is picking up tasks, even if there are more rows to return!

2024/04/05 12:52:50 (worker 1) popped 0 tasks

2024/04/05 12:52:50 (worker 0) popped 0 tasks

2024/04/05 12:52:50 (worker 2) popped 100 tasks

2024/04/05 12:52:51 (worker 1) popped 0 tasks

2024/04/05 12:52:51 (worker 2) popped 0 tasks

2024/04/05 12:52:51 (worker 0) popped 100 tasks

2024/04/05 12:52:52 (worker 0) popped 0 tasks

2024/04/05 12:52:52 (worker 2) popped 0 tasks

2024/04/05 12:52:52 (worker 1) popped 100 tasks

2024/04/05 12:52:53 (worker 0) popped 0 tasks

2024/04/05 12:52:53 (worker 1) popped 0 tasks

2024/04/05 12:52:53 (worker 2) popped 100 tasksWhat’s happening here? By introducing the first CTE, we are now selecting locked rows which are excluded by FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED in the second CTE - in other words, we might not enqueue any runs on some workers if we’re polling concurrently for new tasks. While we are still guaranteed to enqueue in the manner which we’d like, we may reduce throughput if there’s high contention among workers for the same rows.

Unfortunately, using PARTITION BY isn’t the right approach here. But before we dive into a better approach, this query does show some interesting properties of queueing systems more generally.

Aside: queueing woes

A hotfix for the slow polling query would be adding 3 lines of code to our worker setup:

// sleep for random duration between 0 and polling interval to avoid thundering herd

sleepDuration := time.Duration(id) * interval / time.Duration(numWorkers)

log.Printf("(worker %d) sleeping for %v\n", id, sleepDuration)

time.Sleep(sleepDuration)Which gives us much more promising output:

2024/04/05 12:54:19 (worker 2) sleeping for 666.666666ms

2024/04/05 12:54:19 (worker 0) sleeping for 0s

2024/04/05 12:54:19 (worker 1) sleeping for 333.333333ms

2024/04/05 12:54:21 (worker 0) popped 100 tasks

2024/04/05 12:54:21 (worker 1) popped 100 tasks

2024/04/05 12:54:21 (worker 2) popped 100 tasks

2024/04/05 12:54:22 (worker 0) popped 100 tasks

2024/04/05 12:54:22 (worker 1) popped 100 tasks

2024/04/05 12:54:22 (worker 2) popped 100 tasks

2024/04/05 12:54:23 (worker 0) popped 100 tasksThis works — and you can modify this logic to be more distributed by maintaining a lease when a worker starts for a set amount of time — as long as the polling interval is below the query duration time (or more specifically, pollingTime / numWorkers is below the query duration time). But what happens when our queue starts to fill up? Let’s add 10,000 enqueued tasks and run an EXPLAIN ANALYZE for this query to take a look at performance:

QUERY PLAN

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Update on tasks (cost=259.44..514.23 rows=1 width=78) (actual time=132.717..154.337 rows=100 loops=1)

-> Hash Join (cost=259.44..514.23 rows=1 width=78) (actual time=125.423..141.271 rows=100 loops=1)

Hash Cond: (tasks.id = t1.id)

-> Seq Scan on tasks (cost=0.00..254.60 rows=48 width=14) (actual time=0.566..10.550 rows=10000 loops=1)

Filter: (status = 'QUEUED'::"TaskStatus")

-> Hash (cost=258.84..258.84 rows=48 width=76) (actual time=124.155..124.213 rows=100 loops=1)

Buckets: 1024 Batches: 1 Memory Usage: 18kB

-> Subquery Scan on t1 (cost=258.24..258.84 rows=48 width=76) (actual time=123.500..123.791 rows=100 loops=1)

-> Limit (cost=258.24..258.36 rows=48 width=52) (actual time=122.951..123.066 rows=100 loops=1)

-> Sort (cost=258.24..258.36 rows=48 width=52) (actual time=122.830..122.866 rows=100 loops=1)

Sort Key: (row_number() OVER (?)), t.id

Sort Method: top-N heapsort Memory: 36kB

-> WindowAgg (cost=255.94..256.90 rows=48 width=52) (actual time=77.962..111.874 rows=10000 loops=1)

-> Sort (cost=255.94..256.06 rows=48 width=44) (actual time=76.751..79.917 rows=10000 loops=1)

Sort Key: t.group_key, t.id

Sort Method: quicksort Memory: 1010kB

-> Seq Scan on tasks t (cost=0.00..254.60 rows=48 width=44) (actual time=0.093..15.310 rows=10000 loops=1)

Filter: (status = 'QUEUED'::"TaskStatus")

Planning Time: 37.690 ms

Execution Time: 159.286 ms

(20 rows)The important part here is the WindowAgg cost - computing a partition across all rows on the groupKey naturally involves querying every QUEUED row (in this case, 10000 tasks). We expect this to scale sublinearly with the number of rows in the input - let’s take a guess and look at how our workers do on 25,000 enqueued rows:

2024/04/05 13:06:24 (worker 2) sleeping for 666.666666ms

2024/04/05 13:06:24 (worker 0) sleeping for 0s

2024/04/05 13:06:24 (worker 1) sleeping for 333.333333ms

2024/04/05 13:06:26 (worker 0) popped 100 tasks

2024/04/05 13:06:26 (worker 1) popped 0 tasks

2024/04/05 13:06:26 (worker 2) popped 100 tasks

2024/04/05 13:06:27 (worker 0) popped 100 tasks

2024/04/05 13:06:27 (worker 1) popped 0 tasks

2024/04/05 13:06:28 (worker 2) popped 100 tasks

2024/04/05 13:06:29 (worker 0) popped 100 tasks

2024/04/05 13:06:29 (worker 1) popped 0 tasks

2024/04/05 13:06:29 (worker 2) popped 100 tasksSure enough, because we’re seeing execution times greater than 333ms, we start losing tasks on worker 1. This is very problematic, because not only is our queue backlog increasing, but the throughput of our workers is decreasing, and this isn’t a problem we can solve by throwing more workers at the queue. This is a general problem in systems that are stable for a long time until some external trigger (for example, workers going down for an hour) causes the system to fail in an unexpected way, leading to the system being unrecoverable.

A second practical solution to this issue is to create an OVERFLOW status on the task queue, and set an upper bound on the number of enqueued tasks, to ensure worker performance doesn’t drop below a certain threshold. We then can periodically check the overflow queue and place the overflow into the queued status. This is a good idea regardless of the query we write to get new tasks.

But practical advice aside, let’s take a look at how to write this query to avoid performance degradation at such a small number of enqueued tasks.

Improving performance

Sequencing algorithm

The main issue, as we’ve identified, is the window function which is searching across every row that is QUEUED. What we were hoping to accomplish with the partition method was filling up each group’s queue, ordering each group by the task id, and order the tasks by their rank within each group.

Our goal is to write a query that is constant-time (or as close as possible to constant-time) when reading from the queue, so we can avoid our system being unrecoverable. Even using a JOIN LATERAL instead of PARTITION BY will get slower as the number of partitions (i.e. groups) increases. Also, maintaining each task’s rank after reads (for example, decrementing the task’s rank within the group after read) will also get slower the more tasks we add to a group.

What if instead of computing the rank within the group via the PARTITION BY method at read time, we wrote a sequence number at write time which guarantees round-robin enqueueing? At first glance, this seems difficult - we don’t know that Alice will need to enqueue 1 task in the future if Bob enqueued 10,000 tasks now.

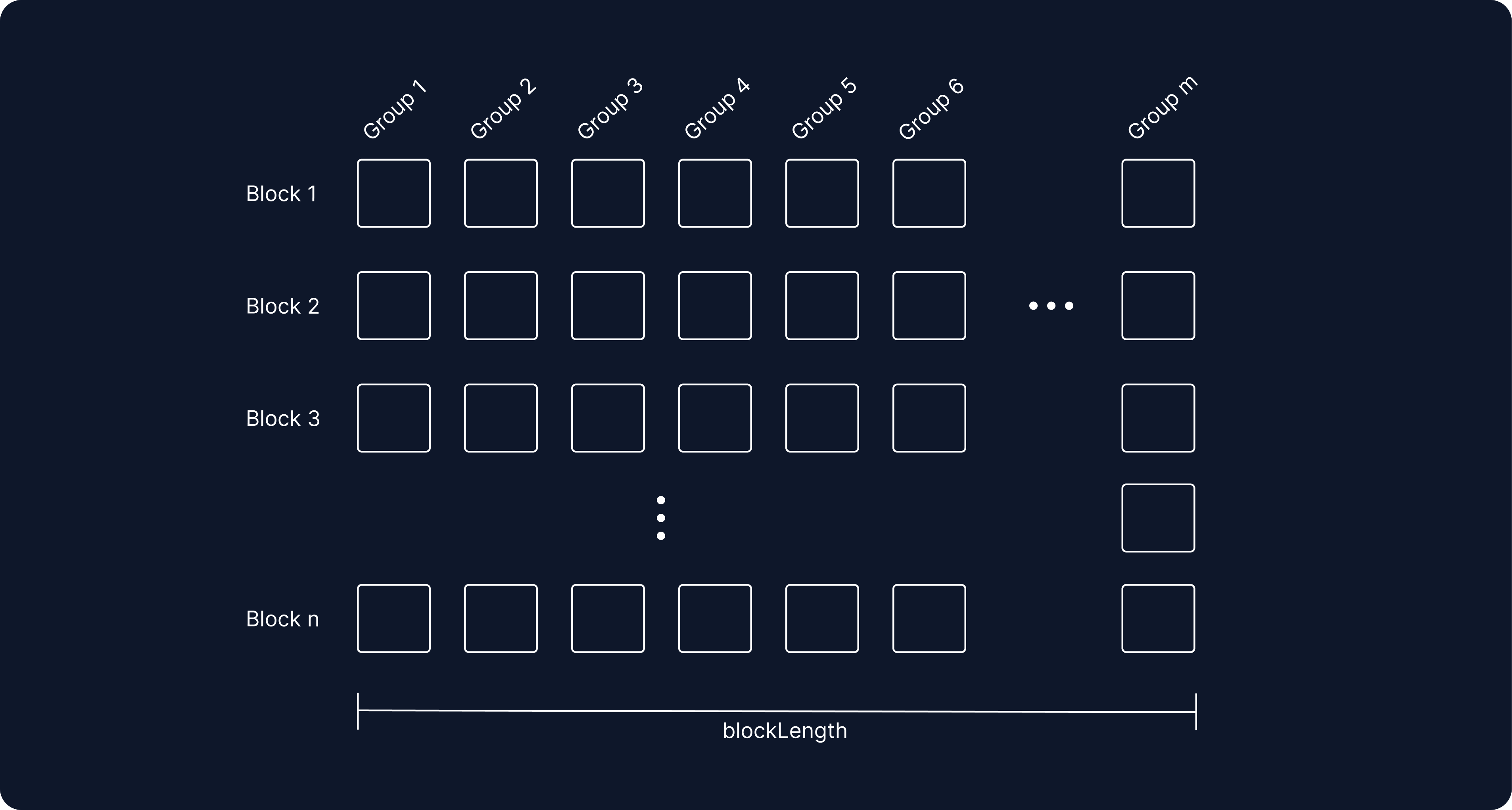

We can solve for this by reserving contiguous blocks of IDs for future enqueued runs which belong to groups which don’t exist yet or don’t have a task assigned for that block yet. We’re going to partition BIGINT (max=9,223,372,036,854,775,807) into blocks of blockLength:

Next, let’s assign task IDs according to the following algorithm:

- Maintain a unique numerical id

ifor each distinct group, and maintain a pointerpto the last block that was enqueued for each group - we’ll call thisp(i). - Maintain a pointer

pto the block containing the maximum task ID which doesn’t have aQUEUEDstatus (in other words, the maximum assigned task), call thisp_max_assigned. If there are no tasks in the queue, set this to the maximum block across allp(i). Initializep_max_assignedat 0. - When a task is created in group

j:- If this is a new group

jis added, initializep(j)top_max_assigned - If this is an existing group

j, setp(j)to the greater ofp_max_assignedorp(j) + 1 - Set the id of the task to

j + blockLength * p(j)

- If this is a new group

*Note: we are making a critical assumption that the number of unique group keys will always be below the blockLength , and increasing the blockLength in the future would be a bit involved. A blockLength of ~1 million gives us ~1 billion task executions. To increase the block length, it’s recommended that you add an offset equal to the the maximum task id, and start assigning task ids from there. We will also (in the worst case) cap out at 1 billion executed tasks, though this can be fixed by reassigning IDs when close to this limit.*

SQL implementation

To actually implement this, let’s add a new set of tables to our queue implementation. We’ll add a table for task_groups, which maintains the pointer p(i) from above, along with a table called task_addr_ptrs which maintains p_max_assigned from above:

CREATE TABLE

task_groups (

id BIGSERIAL NOT NULL,

group_key text,

block_addr BIGINT,

PRIMARY KEY (id)

);

ALTER TABLE task_groups ADD CONSTRAINT unique_group_key UNIQUE (group_key);

ALTER TABLE tasks ADD CONSTRAINT fk_tasks_group_key FOREIGN KEY (group_key) REFERENCES task_groups (group_key);

CREATE TABLE

task_addr_ptrs (

max_assigned_block_addr BIGINT NOT NULL,

onerow_id bool PRIMARY KEY DEFAULT true,

CONSTRAINT onerow_uni CHECK (onerow_id)

);Next, we’ll write our CreateTask query using a blockLength of 1024*1024:

WITH

group_key_task AS (

INSERT INTO task_groups (

id,

group_key,

block_addr

) VALUES (

COALESCE((SELECT max(id) FROM task_groups), -1) + 1,

sqlc.arg('group_key')::text,

(SELECT max_assigned_block_addr FROM task_addr_ptrs)

) ON CONFLICT (group_key)

DO UPDATE SET

group_key = EXCLUDED.group_key,

block_addr = GREATEST(

task_groups.block_addr + 1,

(SELECT max_assigned_block_addr FROM task_addr_ptrs)

)

RETURNING id, group_key, block_addr

)

INSERT INTO tasks (

id,

created_at,

status,

args,

group_key

) VALUES (

(SELECT id FROM group_key_task) + 1024 * 1024 * (SELECT block_addr FROM group_key_task),

COALESCE(sqlc.arg('created_at')::timestamp, now()),

'QUEUED',

COALESCE(sqlc.arg('args')::jsonb, '{}'::jsonb),

sqlc.arg('group_key')::text

)

RETURNING *;The great thing about this is that our PopTasks query doesn’t change, we’ve just changed how we assign IDs. However, we do need to make sure to update task_addr_ptrs in the same transaction that we pop tasks from the queue:

-- name: UpdateTaskPtrs :one

WITH

max_assigned_id AS (

SELECT

id

FROM

tasks

WHERE

"status" != 'QUEUED'

ORDER BY id DESC

LIMIT 1

)

UPDATE task_addr_ptrs

SET

max_assigned_block_addr = COALESCE(

FLOOR((SELECT id FROM max_assigned_id)::decimal / 1024 / 1024),

COALESCE(

(SELECT MAX(block_addr) FROM task_groups),

0

)

)

FROM

max_assigned_id

RETURNING task_addr_ptrs.*;Against 1 million enqueued tasks with 1000 partitions, we still only need to search across 100 rows:

QUERY PLAN

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Nested Loop (cost=12.89..853.72 rows=100 width=77) (actual time=17.521..20.227 rows=100 loops=1)

CTE eligible_tasks

-> Limit (cost=0.42..10.21 rows=100 width=14) (actual time=1.669..16.365 rows=100 loops=1)

-> LockRows (cost=0.42..97842.23 rows=999484 width=14) (actual time=1.662..16.231 rows=100 loops=1)

-> Index Scan using tasks_pkey on tasks tasks_1 (cost=0.42..87847.39 rows=999484 width=14) (actual time=0.711..13.331 rows=100 loops=1)

Filter: (status = 'QUEUED'::"TaskStatus")

-> HashAggregate (cost=2.25..3.25 rows=100 width=8) (actual time=17.299..17.497 rows=100 loops=1)

Group Key: eligible_tasks.id

Batches: 1 Memory Usage: 24kB

-> CTE Scan on eligible_tasks (cost=0.00..2.00 rows=100 width=8) (actual time=1.720..16.959 rows=100 loops=1)

-> Index Scan using tasks_pkey on tasks (cost=0.42..8.40 rows=1 width=77) (actual time=0.022..0.022 rows=1 loops=100)

Index Cond: (id = eligible_tasks.id)

Planning Time: 13.979 ms

Execution Time: 21.433 msYou may also have noticed that because we stopped using the window function, we’ve removed the issue of selecting for previously locked rows. So even if we start 10 workers at the same time, we’re guaranteed to select unique rows again:

2024/04/08 16:28:08 (worker 9) sleeping for 0s

2024/04/08 16:28:08 (worker 8) sleeping for 0s

2024/04/08 16:28:08 (worker 4) sleeping for 0s

2024/04/08 16:28:08 (worker 0) sleeping for 0s

2024/04/08 16:28:08 (worker 1) sleeping for 0s

2024/04/08 16:28:08 (worker 2) sleeping for 0s

2024/04/08 16:28:08 (worker 6) sleeping for 0s

2024/04/08 16:28:08 (worker 3) sleeping for 0s

2024/04/08 16:28:08 (worker 5) sleeping for 0s

2024/04/08 16:28:08 (worker 7) sleeping for 0s

2024/04/08 16:28:09 (worker 1) popped 100 tasks

2024/04/08 16:28:09 (worker 2) popped 100 tasks

2024/04/08 16:28:09 (worker 7) popped 100 tasks

2024/04/08 16:28:09 (worker 0) popped 100 tasks

2024/04/08 16:28:09 (worker 8) popped 100 tasks

2024/04/08 16:28:09 (worker 9) popped 100 tasks

2024/04/08 16:28:09 (worker 3) popped 100 tasks

2024/04/08 16:28:09 (worker 6) popped 100 tasks

2024/04/08 16:28:09 (worker 5) popped 100 tasks

2024/04/08 16:28:09 (worker 4) popped 100 tasksThis doesn’t come without a tradeoff: our writes are slower due to continuously updating the block_addr parameter on the task_group. However, even the writes are constant-time, so the throughput on writes is still on the order of 500 to 1k tasks/second. If you’d prefer a higher write throughput, setting a small limit for placing tasks in the OVERFLOW queue and using the partition method from above may be a better approach.

Introducing concurrency limits

In the above implementation, we had a simple LIMIT statement to set an upper bound of the number of tasks a worker should execute. But what if we want to set a concurrency limit for each group of tasks? For example, not only do we want to limit a worker to 100 tasks globally, but we limit each group to 5 concurrent tasks (we’ll refer to this number as concurrency below). This ensures that even if there are slots available on the worker, they are not automatically filled by the same user, which could again crowd out other users in the near future.

Luckily, this is quite simple with the implementation above. Because of the way we’ve divided task ids across different block addresses, we can simply limit concurrency by searching only from the minimum queued ID min_id to min_id + blockLength * concurrency:

-- name: PopTasksWithConcurrency :many

WITH

min_id AS (

SELECT

COALESCE(min(id), 0) AS min_id

FROM

tasks

WHERE

"status" = 'QUEUED'

),

eligible_tasks AS (

SELECT

tasks.id

FROM

tasks

WHERE

"status" = 'QUEUED' AND

"id" >= (SELECT min_id FROM min_id) AND

"id" < (SELECT min_id FROM min_id) + sqlc.arg('concurrency')::int * 1024 * 1024

ORDER BY id ASC

FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED

LIMIT

COALESCE(sqlc.narg('limit')::int, 10)

)

UPDATE tasks

SET

"status" = 'RUNNING'

FROM

eligible_tasks

WHERE

tasks.id = eligible_tasks.id

RETURNING tasks.*;This guarantees an additional level of fairness which makes it even harder for Bob’s workloads to interfere with Alice’s.

Final thoughts

We’ve covered deterministic round-robin queueing, but it turns out that many systems just need approximate fairness guarantees (“deterministic” in this case refers to the fact that tasks are processed in a deterministic order on subsequent reads - as opposed to using something like ORDER BY RANDOM()). But there are other approaches which provide approximate fairness, such as shuffle sharding, which we’ll show how to implement in Postgres in a future post.

If you have suggestions on making these queries more performant - or perhaps you spotted a bug - I’d love to hear from you in our Discord.

Hatchet Cloud is our managed Hatchet offering. Give it a spin and let us know what you think!