The problems with (Python’s) Celery

Alexander Belanger

Published on June 5th, 2024

Disclosure: I’m a co-founder of Hatchet, a multi-language task queue with Python support. We’re open-source (with a cloud version) and we aim to be a drop-in replacement for Celery that supports a modern Python stack.

Most people who build web apps in Python have encountered Celery. It’s described as a “distributed task queue” — which basically means that it helps users divide background tasks between a set of processes, called workers.

And it’s widely deployed for good reason: it integrates easily into nearly every Python framework, supports a wide range of brokers and backends, and has a number of customization options and higher-order concepts like chains and chords which make it a compelling tool.

While Celery has gotten a lot right, there are many potential pitfalls when using Celery. These come from personal experience — both on the infrastructure and application side as heavy Celery users — along with migrating a number of Celery users to Hatchet. We’ve grouped these issues into 3 categories:

Missing Features

Most people run into the a common set of issues when implementing Celery in a modern Python stack, the most frequent being…

No asyncio support

Celery doesn’t support running async functions as tasks out of the box, and also doesn’t allow created tasks to be awaited. Instead, you’ll have to rely on workarounds like polling for a task result or converting async methods to synchronous ones.

This becomes a significant problem when using Celery for i/o bound tasks which would benefit from asyncio. Given that a very common use-case nowadays is to call external LLMs via a long-lived API call, the lack of asyncio support in Celery is a major drawback.

While the Celery maintainers have been promising implementation on this front for a while, there isn’t any external indication of progress. At some point, the maintainers seemed to indicate that this was related to a Celery project called Jumpstarter, which there is very little information about beyond issues filed in the repo.

There have been some mentions of this being available in Celery 6.0 or Q3/Q4 2024, but there isn’t much information outside of this. There’s also an open issue from an external contributor with a barebones implementation of an AsyncIO pool which seems promising.

To track the open issues:

No global rate limiting

As soon as you have pool of workers, a common pattern is to enforce a global rate limit across all workers in the pool. For example, if each of your tasks is calling an external API, the API will typically enforce a rate limit across all requests.

This isn’t possible in Celery — only rate limits per worker or per task are supported. The docs state the following:

Note that this is a per worker instance rate limit, and not a global rate limit. To enforce a global rate limit (e.g., for an API with a maximum number of requests per second), you must restrict to a given queue.

Contrary to the docs, it seems that you can’t set this at the queue level for multiple workers consuming from that queue.

Another small nit: the rate limiting is implemented as a delay in picking up new tasks, evenly distributed across the timeframe. So if there’s a considerably low limit, say 10/hour, tasks can run at most once every 6 minutes. From the docs:

Tasks will be evenly distributed over the specified time frame. Example: “100/m” (hundred tasks a minute). This will enforce a minimum delay of 600ms between starting two tasks on the same worker instance.

This most likely isn’t how rate limiting is implemented on your third-party provider. The most common behavior is that the rate limit corresponds to the total number of requests allowed within the timeframe - so it won’t matter whether it’s 10 requests at the start of the hour, or 10 requests spaced evenly throughout the hour, and with an even distribution you may be unintentionally bottlenecking your workers.

No first-class support for dead-lettering

Dead-lettering is a common pattern in message queues, where messages which can’t be processed are moved to a separate queue for later inspection. This is useful for debugging, as well as for handling messages which are failing repeatedly.

Unfortunately, Celery doesn’t have any first-class support for dead-lettering, with the docs directing you to use the underlying broker’s dead-lettering feature. Not only does this significantly reduce interoperability between brokers (and would involve quite a bit of custom logic to configure in Redis), but also involves becoming familiar with the broker’s queue configuration, which should be offered as part of the Celery abstraction.

No task-level concurrency settings

I’ve written previously about the use-case for multi-tenant queues — particularly how to implement fair queueing strategies so that a subset of users don’t crowd out other users in the system.

A common pattern is to limit concurrency per user or tenant, which is commonly implemented through workers consuming from multiple queues. While it’s possible in Celery to limit concurrency on a per-worker basis, and even create queues and assign them to workers programmatically, it’s not possible to set a concurrency limit on tasks themselves, which means there’s a high risk of unfair task assignment between queues.

A quick aside — this behavior will vary depending on which broker is used. RabbitMQ will round-robin across many FIFO queues. This doesn’t seem to occur in Redis.

Even if our broker does support round-robin enqueueing, not being able to set a concurrency limit for a task can lead to unfair situations because of future work constraints. For example, say we have 100 workers. User A enqueues 100 long-running tasks, and a short while later User B enqueues 1 long-running task. All workers will have picked up the 100 tasks from User A, meaning that User B is crowded out of the system (despite having round-robin enqueueing).

Ideally, we could set a concurrency limit per user which is significantly smaller than the limit across all workers. This behavior becomes more severe using Redis as a broker or a high prefetch limit.

ETA tasks reside in memory

The behavior of ETA or countdown tasks is to get assigned to a worker and reside in worker memory until they’re ready to be processed. While this is a consequence of the design choice to have a single broker dependency with no central scheduling component, this can cause high worker memory usage and reports of high broker load as well.

Questionable Defaults

Creating defaults is a difficult problem — there is no one-size-fits-all setting for all types of workloads which may use a task queue. That said, some of the defaults in Celery are almost completely undocumented, with no indication of the tradeoffs of enabling one or the other — and other defaults seem to be more commonly changed than not.

Heartbeat/Gossip/Mingle

Let’s start with the most egregious example — if you take a look at the CloudAMQP docs for running Celery, they recommend running Celery with the following flags:

--without-heartbeat --without-gossip --without-mingleNote that these arguments aren’t explained in current Celery docs, but when running with many worker processes, turning off these arguments can save a huge amount in data transfer costs. The reason is primarily due to the gossip feature subscribing to every other worker’s events, which scales by n^2 as the number of workers increases. With this amount of network overhead, this feature must be important, right? According to the Celery 3.1 release notes:

This means that a worker knows what other workers are doing and can detect if they go offline. Currently this is only used for clock synchronization, but there are many possibilities for future additions and you can write extensions that take advantage of this already.

Some ideas include consensus protocols, reroute task to best worker (based on resource usage or data locality) or restarting workers when they crash.

We believe that although this is a small addition, it opens amazing possibilities.

Note that clock synchronization is only important in Celery when using ETA/countdown features, which you probably shouldn’t be using anyway.

Losing Tasks by Default

The default behavior of Celery is to prefetch tasks from the broker with “early acknowledgement” turned on, which means that it acknowledges the task as soon as it starts executing the task. This means that if the worker crashes halfway through a task execution (for example, you redeploy the worker without graceful shutdown), the task won’t be retried on a different worker — from the broker’s perspective the task is completed. The Celery docs say the following on the matter:

So for ease of programming we have less reliability; It’s a good default, users who require it and know what they are doing can still enable acks_late (and in the future hopefully use manual acknowledgment).

Sure, there’s no tradeoff-free approach to this problem, as there’s no such thing as exactly-once delivery when dealing with a network that isn’t 100% reliable. But “reliability vs ease of programming” is a false equivalency for a few reasons:

- The decision to set this default, along with the decision to not surface an error when a worker restarts and reconnects, makes programming more difficult. Debugging behaviors involving the absence of a task is much more difficult than debugging failures involving multiple task executions - the absence of a task execution (or a task in a perpetual “Started” state according to

celery.events) lives outside the purview of the application, and won’t be captured by typical logs or failure events instrumented by the application developer. - It’s far more common for a task queue to implement at-least-once execution with idempotency (known as effectively once) than at-most-once execution. If we wanted at-most-once execution, the simplest approach would be a pub/sub system without message persistence.

We usually recommend to set acks_late to True.

Worker Prefetch Count

One of the most common complaints we hear from people who are just getting started with Celery is that they’re having performance issues. These are generally applications whose tasks are high latency or highly variable in duration.

The reason for many of these complaints comes down to the prefetch multiplier:

The workers’ default prefetch count is the

worker_prefetch_multipliersetting multiplied by the number of concurrency slots (processes/threads/green-threads).

The default value is 4, which means that each worker can pull in up to 4 times the number of worker processes available. Let’s take a look at what this looks like when we have a single long-running task with a bunch of shorter-running tasks:

The reason for this default is performance — prefetching tasks means that the worker doesn’t need to make a round-trip request to the broker whenever it’s ready to execute tasks.

But this only becomes a considerable factor when the duration of a task is within an order of magnitude of the round-trip latency. And since the broker is typically running in the same datacenter as the application itself, and RabbitMQ (the default broker) can achieve < 1ms latency. So if your tasks are doing a single database read or write, then you probably want the prefetch limit to be higher.

But on average, there’s a good chance that this will degrade performance, since the work can become very unbalanced between workers. For example, during a rolling redeployment, the first worker which comes online might pull in all active tasks in the queue, leaving the other workers to process tasks on-demand.

As a result, if your tasks run for more than 100ms and are variable in duration, we usually recommend setting worker_prefetch_multiplier to 1 in Celery.

Lack of Default Task Timeouts

There’s no better way to overflow a queue than to risk tasks executing for a long period of time. Or, perhaps not an overflow, but a queue depth which is essentially irrecoverable, because to reduce the bottleneck you’d need orders of magnitude more workers, connections, etc.

We’d advocate for something somewhat unintuitive here: a default 1-minute timeout on task executions. This is well within the range of many tasks which are meant to execute quickly (for example, simply call a set of third-party APIs), but the timeout will be surfaced during development for anything which is expected to be longer-running, which means the developer will be aware of and required to set a timeout.

Observability

It’s arguably more important to invest in an observable system than a fully reliable one. Failures should be expected in software — sometimes they can be handled gracefully, with retryable exceptions — or sometimes a failure is fatal, and we simply need to send an alert to an engineer to fix the problem.

There are a few options when it comes to monitoring Celery, the most common that we’ve seen being Flower or a Prometheus → Grafana configuration (of which there are a few options). These tools rely on the celery.events API and are flawed for different reasons.

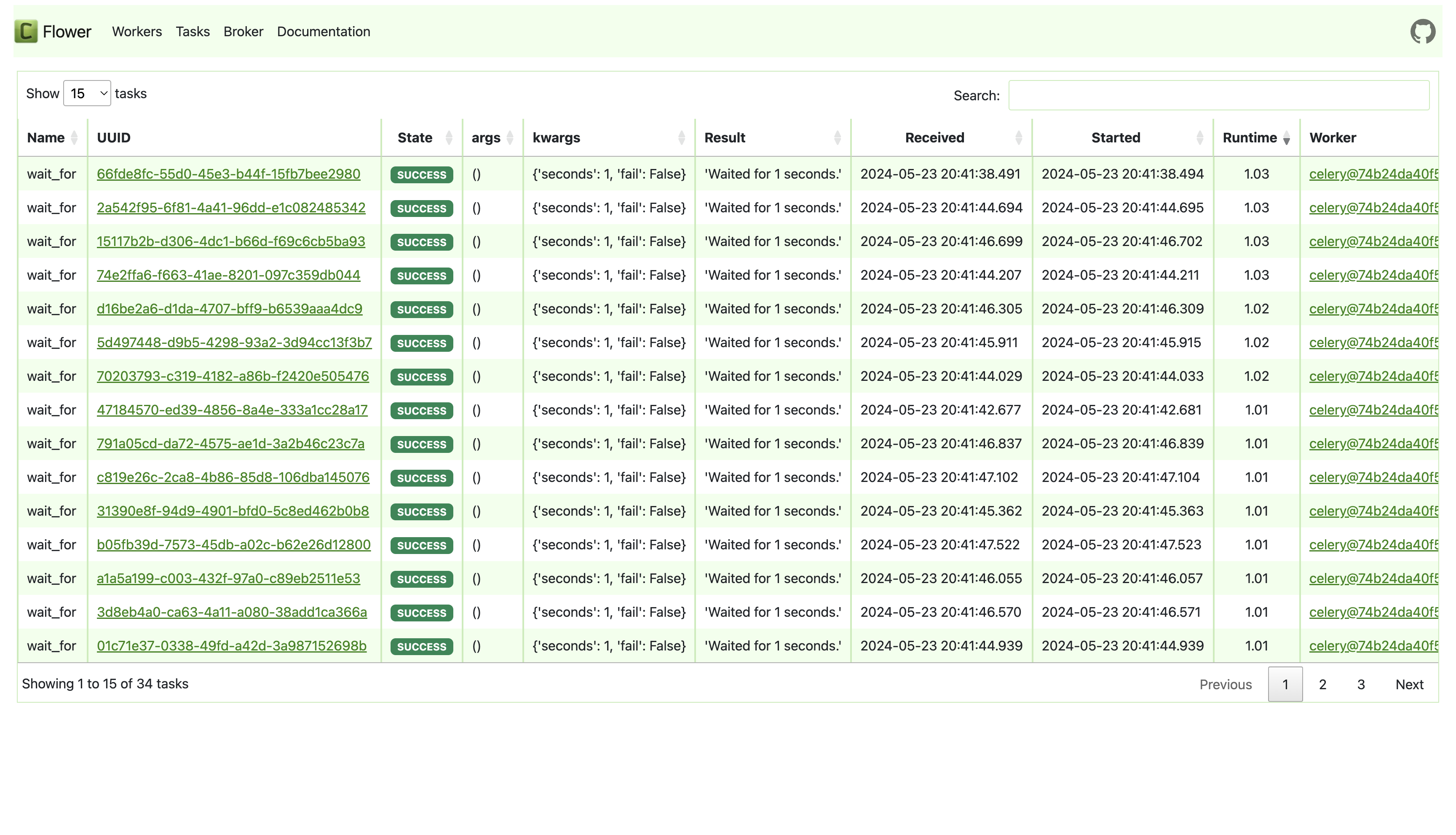

Let’s start with Celery Flower. The default tasks view looks something like:

Celery Flower works by listening for celery.events and persisting them to an in-memory store or an optional persistence database. But it does not support reading tasks from a Celery backend (which is used to persist tasks) — which means that at best, you’ll be storing duplicated tasks data across two data sources, and at worst (and more likely, the expected case), you’ll miss Celery tasks when Flower goes down or restarts. This long-standing issue with Flower can be tracked here: https://github.com/mher/flower/issues/542.

Beyond that, the Flower UI isn’t mature enough to be helpful in a high-load scenarios when you are more interested in aggregate views across your tasks. For example:

- Which tasks failed in a certain time range?

- When did I see a spike in task latency?

- Do any workers have a high task failure rate?

These are precisely the types of questions that a Celery → Prometheus → Grafana integration would answer. But here — beyond the tedium of setting up plumbing and questioning why Prometheus needs 15 GB of memory for a handful of metrics — we have the opposite problem. Once we identify a failure, drilling down into the actual failure reason is annoyingly difficult. The Prometheus metrics exporters won’t give you details on kwargs or results, so you’ll need to go back to your Celery task backend and do your own digging after identifying a failure.

A quick aside — a promising solution is instrumentation using OpenTelemetry Celery. This aims to be the best of both worlds: most otel providers are able to drill down to provide details on individual traces from an aggregate view. But for the level of granularity provided by Flower, you’d likely need to instrument your functions manually.

And this doesn’t even include basic alerting, which would involve setting up triggers in a tool like Honeycomb or configuring alert-manager rules with Grafana.

At this point, we’re putting in some legwork — building and maintaining our own dashboards and alerts — for what is a set of very basic features (aggregate views and good filtering across persisted tasks).

If you’ve read this far, perhaps you’d be interested in how we’re solving some of these problems with Hatchet. The reason we can avoid certain classes of problems is that we have a central component (our “engine”) along with a Postgres database for result persistence, which makes it much easier to implement global rate limits, worker management (no n^2 networking issues), and lets us persist ETA tasks instead of having to pull them off the queue immediately.

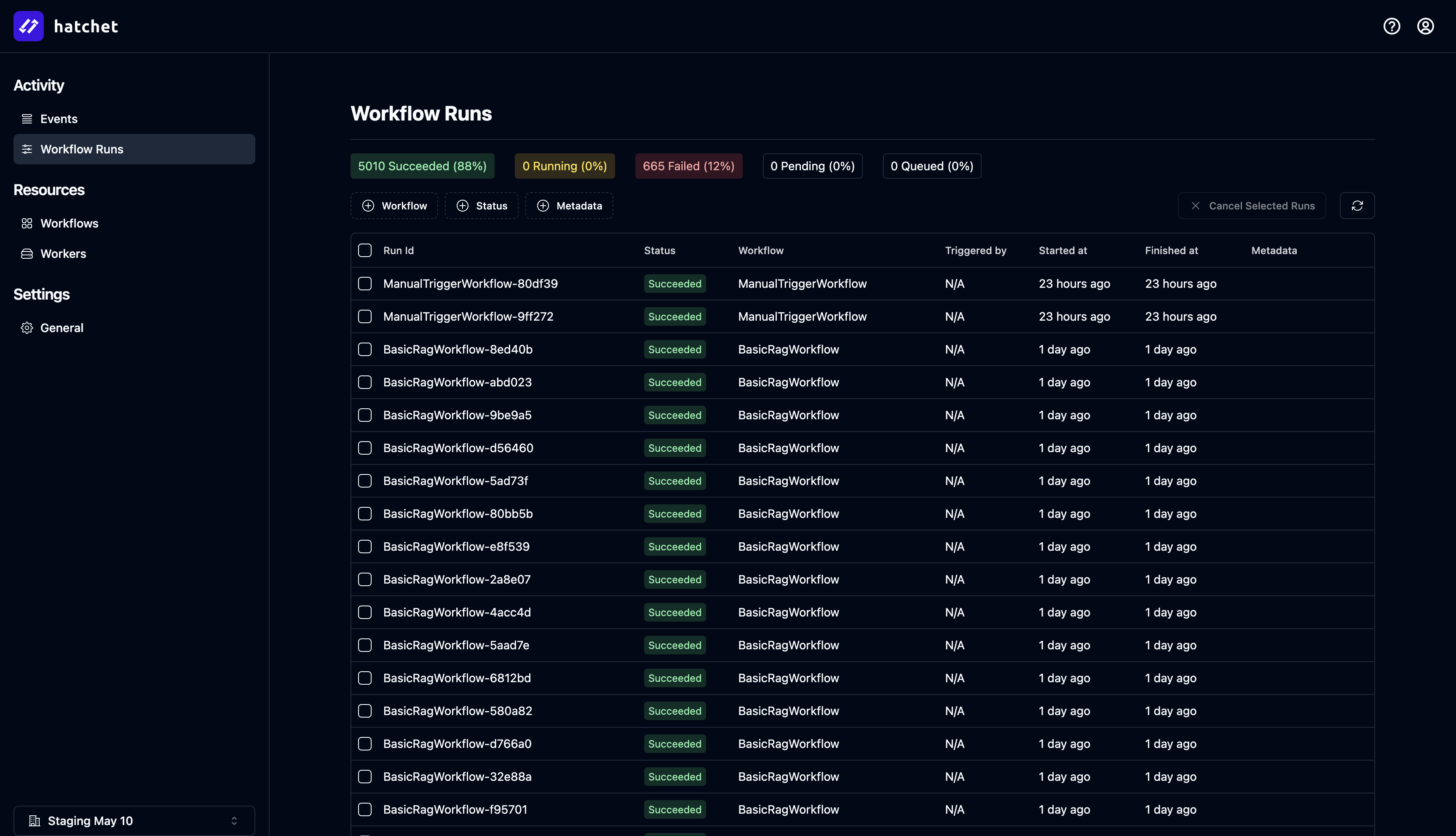

Observability with dashboards and alerting is also a first-class citizen of Hatchet. We currently support Slack and email-based alerts on failure, and we have a feature-rich UI which lets you debug and filter your tasks:

All that said, we’re still an early project, and are actively working on aggregate metrics views and first-class support for dead-lettering. If you have a feature request, please let us know in our Discord.

If you’d like to give us a try, you can get up and running in 5 minutes with Hatchet Cloud.